Emeritus Professor Dr Konrad Kwiet

Adjunct Professor for Jewish Studies and Roth Lecturer in Holocaust Studies, The University of Sydney and Resident Historian at the Sydney Jewish Museum

Studying Leni Riefenstahl and Albert Speer

The Nazi Ruling System

Nazi Germany was a dictatorial Führer-State and a popular Volks-State. The racist regime that had replaced the Weimar Republic rested on several ‘pillars of power’2. These were intertwined, often competing with each other to defend or expand their spheres of jurisdiction. The peculiar structural make up of this ‘polycratic’ system was based on a ‘pact’ between National Socialism, the social-conservative elites and the populace3. The alliance ensured the effective functioning and ongoing dynamics of Nazi rule. At the top stood Adolf Hitler4, Führer und Reichskanzler, the charismatic Leader and omnipotent Reich Chancellor, firmly integrating the Volk into the Führer-State. The Nazi leadership was in command of the Party apparatus and its numerous organisations.

In merging Party and State, Nazi leaders and NSDAP officials took over command posts within the traditional system of government and administration. They relied on the expertise of the social-conservative elites, most of whom retained after the Nazi ‘revolution’ of 1933, leading positions in all sectors of society – ranging from civil service via the military and business to the worlds of arts and culture, education and health care. The introduction of the ‘Aryan Paragraph’ and subsequent professional bans enforced the removal of Jews and other opponents. The regime was attractive. It offered the opportunity to embark on rapid and prestigious careers, in particular for young and ambitious professionals from whose services it could reap benefit.

Albert Speer and Leni Riefenstahl fall into this category. Both were great admirers of Adolf Hitler who, attracted by their talents and skills, commissioned them with tasks, which earned them the reputation of being not only confidantes and protégés of the Führer but also icons and celebrities of the Führer-State. Table I reveals the place they occupied within the Nazi ruling system.

Propaganda and Terror

Propaganda and Terror served as instruments to establish and secure the ‘New Order’ in which there was no place for those branded as Volks- und Reichsfeinde, the ‘Enemies of the German People and Nation’5. They were punished. The sanctions ranged from imprisonment and incarceration in concentration camps to murder.

Heinrich Himmler, Reichsführer-SS and Chief of the German Police, was entrusted with the task of persecuting all opponents and implementing the program of the ‘Final Solution’. The terror against the Jews and other victim groups had a deterrent effect upon the population. ‘Ordinary People’ witnessed their ejection from society and disappearance and either suspected or knew of their fate. However, they did not acknowledge it.

Propaganda and Indoctrination provided the population with the satisfaction of belonging to the Volksgemeinschaft. This identification excluded any solidarity, any expression of partiality with those targeted for persecution and murder (See Table II). To the bitter end, the vast majority of Germans identified themselves with the Nazi Regime and their beloved Führer. “Das haben wir nicht gewußt!” “We knew nothing about it!” That was the widespread claim among the German population before and after 1945. As the German historian Wolfgang Benz states, ‘What for many was self-protection turned into the greatest sham of a generation after the collapse of the Hitler state”6.

Leni Riefenstahl and Albert Speer helped to disseminate and cement historical lies and legends and, in so doing, provided many with a most welcome alibi: If Speer and Riefenstahl professed ignorance how could ‘ordinary’ people have known of the murder of Jews?

Leni Riefenstahl 1902-2003

Within Joseph Goebbels’ empire of propaganda and indoctrination Leni Riefenstahl emerged as the favourite filmmaker of the Nazi regime. She was a brilliant artist and skillful propagandist who, from the beginning, aroused considerable debate.

She began her career as dancer, actor and film director of the new genre of ‘Mountain’ films that attracted Hitler’s admiration. After the ‘seizure of power’ in 1933, when her Jewish colleagues and friends were banned from the world of culture and forced into exile, she accepted Hitler’s offer to make films documenting the power, glory, and mission of Nazi Germany. She enjoyed the prestige, popularity and the prizes awarded to her for her films – both in Germany and abroad.

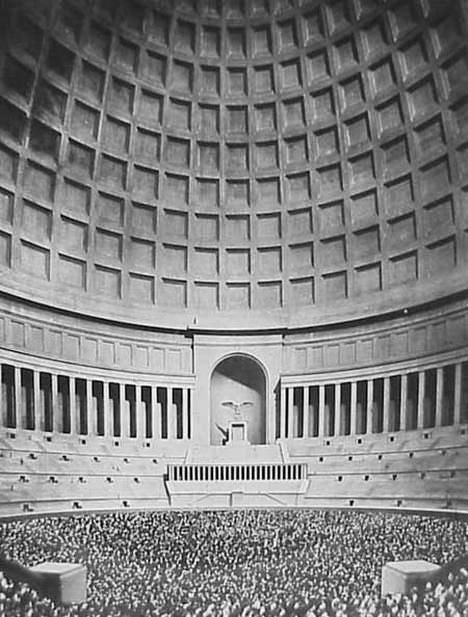

She operated in an industry dominated by men. Introducing pioneering camera techniques and using the latest production technologies she created masterpieces of film propaganda that became milestones in the history of cinematography7. Some critics argue they are the best propaganda films ever made. Her black-and-white documentaries of the 1934 Nuremberg party rally (‘Triumph of the Will’) and of the 1936 Berlin Olympics brought her ‘pre-war acclaim and post-war infamy’. ‘Triumph of the Will’ captured the grandeur and orchestration of Nazi rallies and rituals. At its centre stood the deification of Adolf Hitler and – in all her works and throughout her life –fascination with the concepts and Fascist images of ‘Youth’, ‘Body’ and ‘Beauty’.

After the war Leni Riefenstahl was categorised by a de-nazification tribunal as a Nazi ‘sympathizer’. She retreated into a self-imposed exile in an attic of a Munich house. In the 1960’s she reinvented herself and reemerged as a photographer who depicted the exotic life of the Nuba tribe in Sudan and then the colourful underwater world of barrier reefs.

Haunted by the past, accused of being a Nazi, seducer, liar, denier, anti-semite and mistress of Hitler, Goebbels and other Nazi leaders, she sought to clear her name and to defend her films. She defined her films as ‘works of art’8 and claimed that they had nothing to do with Nazi politics and propaganda. She never offered an apology for her involvement with the Nazis. She insisted that she had never been a member of the Nazi party, let alone an anti-semite or mistress of Nazi leaders. Like many others, she maintained that she had known nothing about the slaughter of 6 million Jewish men, women and children.

In her final years she reappeared in public and social life mixing with celebrities of sports and culture including tennis player Boris Becker and actors Madonna and Jodi Foster. She enjoyed the reputation of “feminist pioneer”. Leni Riefenstahl died in Berlin in 2003, at the age of 101. Her death re-ignited the old controversy surrounding her ‘Horrible and Beautiful Life’9. There are signs that with the passage of time her life and works will be viewed in a more positive and forgiving light.

Albert Speer 1905-1981

Albert Speer fulfilled all tasks assigned to him with utmost efficiency10. In 1931, attracted by Hitler’s charisma and ideas, he joined the Nazi party, which honoured his entry by commissioning him with construction projects. Speer commenced his career as a young architect re-designing Party and State buildings. Subsequently in Nuremberg he established his reputation for outstanding organizational skills. Speer was the mastermind behind the staging of the Party rallies. In 1937 he was entrusted with translating Hitler’s dream of world domination into architectural drafts. His drawings and models of monumental buildings, squares and parade grounds symbolised the horrific landscape of the envisaged ‘world order’.

In 1941 – in the process of re-developing Berlin as future capital of the world ‘Germania’ – he became a driving force behind the removal of Jews. 72,000 Jews were forced out of their homes and deported to the newly conquered territories in East Europe. Speer knew that they would never return. In 1942, when the race war was in full in swing, he was appointed as Minister for Armaments and War Production. In this capacity he was in charge of the exploitation of a vast army of slave labourers and inmates of concentration camps. Many fell victim to a genocidal strategy termed by the Nazis as ‘destruction through work’.

Nazi architechture by Albert Speer (l) and Speer with Hitler (r)

Nazi architechture by Albert Speer (l) and Speer with Hitler (r)

Speer served as ‘Schreibtischtäter’, a ‘desk killer’, the technocrat of genocide. On the eve of the ‘unconditional surrender’ of Nazi Germany he attempted to sabotage Hitler’s ‘scorched earth policy’ hoping to save remnants of the infrastructure for the post-war reconstruction of Germany. Finally, in April 1945 he still found his way through the ruins of Berlin to pay a final farewell to his close friend and beloved Führer.

Unlike Adolf Hitler and other Nazi leaders, Albert Speer did not take the path of suicide to escape criminal prosecution. The International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg sentenced him to 20 years imprisonment. After his release from Spandau prison in 1966, he embarked on a second successful career – as writer and propagandist. He hastened to write his memoirs, which caused a furor and became an international bestseller11. Other books, lecture tours and interviews followed.

Speer emerged as the most important living-witness of the History of Nazi Germany. He portrayed himself not only as a ‘Good German’, an angel returning from hell, but also as a ‘Good Nazi’ who showed remorse and admitted collective responsibility for the heinous crimes committed. However, referring to the secrecy imposed upon the program of the ‘Final Solution’, he maintained ignorance and innocence of the murder of the Jews. Even when he was confronted with the historical revelation that he must have listened in October 1943 to the speech of Heinrich Himmler on the extermination of the Jews, he continued to deny knowledge of the Holocaust. The closest he came in his constant “battle with truth”12 was the admission of guilt of not having wanted to know and, in doing so, giving tacit approval to ‘the persecution of the Jews and the murder of millions of them’13.

In the final years of life Albert Speer found self-fulfillment in the form of a love affair with a much younger woman. He died in London in 1981 – aged 76. He continues to arouse heated debate at public and academic levels. The old images of the “Good German” and “Good Nazi” are being overtaken by the portrayal of a Nazi leader serving as architect of a racist ‘world order’, as a highly efficient organiser of total war and as a technocrat of genocide.

Editorial Note

The Sydney Jewish Museum offers seminars on Leni Riefenstahl and Albert Speer conducted by Professor Konrad Kwiet. The seminars provide an historical framework within which the personalities of Riefenstahl and Speer are critically examined. Excerpts from two TV documentaries are shown depicting the lives and careers of each historical personality within Nazi and post war Germany. During the Museum visit, students have the opportunity to hear Holocaust Survivor testimony. The focus of the Museum tour is on Syllabus outcomes including gathering information from different sources and analysing and evaluating sources for their usefulness and reliability.

This article first appeared in Teaching History, Journal of the History Teachers’ Association of NSW.