by Konrad Kwiet

Conceptual Framework

Horrific crimes against humanity, unprecedented in history, were committed during World War II. On the continent of Europe they culminated in the slaughter of 6 million Jewish men, women and children, celebrated by the genocidal murderers as the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question”. Today we call the Nazi genocide of European Jewry, inaccurately, the Holocaust. It is a word that derives from a Greek term originally meaning a “sacrifice totally burned by fire”, “a burnt offering to God”. More accurate is the term Shoah, the Hebrew word for catastrophe. Holocaust scholarship has become highly specialized, fragmented and divided by national and linguistic barriers.

Despite an immense, ever-increasing corpus of Holocaust literature, many areas and topics are still unexplored. The key question “Why?” remains answered. At the same time, the relationship between the murder of the European Jews and genocide persists as a contentious issue that, far beyond the circle of historians, sociologists and political scientists, affects our ability to grasp the meaning of the past as well as current events. No model of interpretation, and none of the theories on the nature of Fascism or National Socialism, antisemitism or racism, totalitarianism or modernity can adequately explain the annihilation of European Jewry. However an historical framework can be set up which allows us to shed some light on the basic patterns of Nazi policies and to determine the significance of the assault on Jews.

Pattern of Nazi Policies

The genocide of European Jewry was the central component of the Nazi quest for a Greater Germanic Empire. A new world order dominated by Germany was to be established, based on the “Aryan master race”. Racial doctrines dictated the conquest of new “living space” in Eastern Europe and the enslavement of the population in all occupied territories.

From the outset in 1919 Adolf Hitler, the Führer, the Leader of the Nazi party, propagated the central idea that the final aim of the Nazi Jewish Policy must be the “complete removal of the Jews”. This “Final Solution of the Jewish Question” was more than a purification process. Jews were depicted as world enemies endangering the survival of the German “Aryan” world. The race fanatics believed that “Jewish ideas” had shaped liberalism and democracy, socialism and bolshevism. Both Jews and “Jewish ideas” had to be eliminated in order to secure the “new order” in which there was no place for any person or group regarded as a political, social or racial enemy. Indeed, this blueprint for a new society and the policies pursued to achieve it represented a clear caesura in the history of civilisation.

Antisemitism, embedded in German and European history and culture, served alongside racism as the core of the ideological driving force; Jew-hatred was the indispensable precondition for mass murder. Nazi propaganda and indoctrination helped create the foundation on which state sanctioned crimes could be conceived, planned and carried out. They did not only target the victim groups – the “Enemies of the German People and the Germanic Empire” – but also determined the thinking and behaviours of both perpetrators and “bystanders”.

Bystanders to the Holocaust included Allied governments, neutral powers, international agencies, churches and the vast majority of the population in Germany, in Nazi occupied territories and in countries of the free world. They responded to the Holocaust with indifference, silence and denial. In Germany, the architects and executors of the “Final Solution” could look confidently towards cooperation from the social-conservative elites and on broad support from the general population. It was the absence of resistance that enabled and encouraged the Nazis to implement the program of the “Final Solution”. Raul Hilberg, the doyen of Holocaust research, offers a classic model of description and interpretation . Placing the Holocaust within the bureaucratic framework of the modern state, he sheds light on the policies of mass destruction and the various stages of the process of destruction.

Process of Destruction

Immediately after Hitler’s seizure of power in 1933, the Nazis set about destroying the basic conditions for the continued existence of the Jews in Germany. They fulfilled the old promise of the Kampfzeit – the “time of struggle” during the Weimar Republic – to force the Jews out of the economy and society and effect a Reinliche Scheidung, the “clear parting of the ways” of Jews and Germans.

In the pre-war years – against the backdrop of the creation the Deutsche Volksgemeinschaft – the national community – the Nazis propagated a “traditional solution” of the “Jewish Question”: either social segregation within Germany or expulsion from its borders. The latter was the preferred Nazi alternative. The measures employed included anti-Jewish laws and regulations such as the Nuremberg race laws of 1935, boycotts and periodically organised outbursts such as the November pogrom of 1938, commonly known as “Kristallnacht.” Defamation and discrimination, expropriation and expulsion took place in public . The Nazis created a decimated, impoverished Jewish community, stripped of all rights and restricted in their movements: a group of “social dead”, a burden to German “Aryan” society, a community they could dispose of in secrecy.

With the invasion of Poland in September 1939 the persecution of the Jews was transferred to the occupied territories and radicalised. The Nazis embarked on large-scale re-settlement projects. A second, brief period, covering the years 1939 – 1941, marked the transition to mass murder . In Germany the killing of handicapped people, considered as “unworthy for life” and threatening the purity of the “Aryan master race”, commenced. Carried out in secrecy, the so-called Euthanasia program provided personnel and techniques for the murder of Jews.

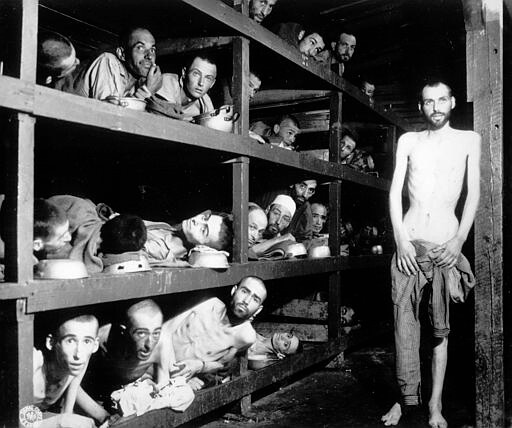

For a short period the possibility of a “territorial solution” of the “Jewish Question” was considered. Plans were discussed to remove Jews to the island of Madagascar or to other remote “Jewish settlements”. In occupied Poland Jews were herded together in ghettos, subjected to terror and slave labour, appalling hygienic conditions, starvation and disease . The destructive dynamic of Nazi Jewish Policy very quickly reached the point where the traditional catalogue of enslavement was exhausted. When this became clear, the “Final Solution”, in the form of systematic extermination, presented itself as the last and logical step to remove the Jews once and for all.

The attack against the Soviet Union in June 1941, code-named Barbarossa, signaled the prelude to the Holocaust. The first wave of killing in the newly conquered territories in the East resulted in the murder of more than 700,000 Jews. The genocidal campaign targeted Jews regardless of age and gender. In October 1941 the Nazis imposed a ban on emigration. Expulsion was replaced by extermination. In the Soviet Union, executions in the form of open-air shootings remained the dominant pattern of mass murder. Extermination camps, equipped with modern and more efficient killing technologies – gas chambers and crematoria – were set up in occupied Poland. Jews in Central and Western Europe were rounded up and deported to death factories operating in Chelmno and Belzec, Treblinka and Sobibor, Maidanek and Auschwitz-Birkenau, the epicenter of the Holocaust .

Profile of Perpetrators

Within the Nazi machinery of mass destruction representatives of many walks of life carried out their duties with the utmost efficiency – Germans and non-Germans alike. (Table III) The total number of perpetrators surpassed 500,000. Among them were Protestants, Catholics and members of other Christian churches together with confirmed disbelievers. The age of Nazi killers ranged from young recruits to the elderly. They represented all social strata and professions. They were almost exclusively male. Fewer than 5, 000 women were recruited to serve in the police force or to function as SS-Aufseherinnen, concentration camp guards whose duties included acts of torture and murder.

Expertise was offered by individuals and professional groups such as doctors and scientists, academics and lawyers, architects engineers and bureaucrats. One particular group played a pivotal role – Schreibtischtäter – the “desk murderers” – serving as the technocrats of genocide. The murderers wore an array of different uniforms. From the ranks of Heinrich Himmler’s SS and police came the ideological warriors or genocidal killers serving with the Security Police, Security Service, regular Order Police and the Waffen SS, the armed SS. The Wehrmacht became an integral part of the “Final Solution”. If the combined manpower of SS, police and the military was not available or sufficient to carry out the Judenaktionen – the “actions” taken against the Jews – officials from other Nazi agencies served as substitute killers. Finally, there was a vast army of genocidal killers of other nationalities. Local collaborators were often entrusted with the dirty work, the murder of women and children or with the guarding of ghettos, slave labour camps and death factories. In many cases, they surpassed their German masters in cruelty and spontaneous brutality.

National or religious, social or professional, ideological or institutional ties can neither explain the ability to commit mass murder nor the satisfaction derived from it. The American historian Christopher R. Browning has coined the notion of “ordinary men”, who became perpetrators, less as a result of ideological than of situational forces such as group pressure, blind obedience, the war situation and career advancement . The American political scientist Daniel Jonah Goldhagen insists on a purely ideological driving force for mass murder, namely an “eliminationist antisemitism” . Emerging in the 19th century, this special brand of German antisemitism equipped “Hitler’s Willing Executioners” with the drive to kill the Jews. It also created a willingness on the part of “ordinary Germans” to accept the murder of six million Jews as a “national task”, and even to applaud the slaughter. The debate surrounding “Hitler’s Willing Executioners” and “ordinary Germans” perpetrating the murder of the Jews continues to this day.

Rehearsing for Murder

“Ordinary men” were not born as genocidal killers. Virtually none of them knew prior to their recruitment that they would be asked to kill Jews or other enemies. However, they quickly grew accustomed to the routine. The gradual process of “rehearsing for murder” was facilitated by exercises designed to strengthen group bonds and to ensure conformity to Nazi ideology, especially antisemitism. Language regulations demanded the use of euphemism to disguise the reality of killing. Orders were given sanctioning Judenaktionen. They also radicalised the decision making process of the “Final Solution”.

Adolf Hitler did not issue a general order to kill all Jews. His “will” and “wish”, documented and often quoted, were sufficient to commission Nazi leaders and, above all, Heinrich Himmler, Reichsführer-SS and chief architect of genocide, to prepare and implement the “Final Solution”. Basic decisions were made at the highest level of leadership and handed down through clearly defined channels of command. Nazi officials at the middle level of leadership were granted sufficient leeway to initiate more radical and ruthless measures at their own discretion. Regional and local SS and police commanders, at the scenes of the crimes, often competed to secure and expand their spheres of jurisdiction.

Efforts were made to speed up the process of liquidation, that is, to declare their areas judenfrei, “free of Jews”, as quickly as possible. Nothing mattered except a report of success. On the lowest level, the rank and file of the genocidal apparatus, the foot soldiers, offered through their actions the clearest evidence that horrific crimes could become reality. Little time passed before local and individual initiatives received official sanction and were incorporated within revised guidelines, which in turn resulted in the escalation of total destruction. Thus decisions were made not only at the centre – in the Führer Headquarters, they were also made at the periphery, at the killing fields of the Holocaust, a fact that accelerated the process of mass murder and contributed decisively to the realisation of the genocidal aim. It also helped to accelerate the transformation of “ordinary men” into genocidal killers.

These strategies were rewarded. As a result of their preparation for and practice in murder, perpetrators very quickly displayed modes of behaviour which were symptomatic of the destruction of all moral and human values. Brutalisation and dehumanization resulted in a deadening of any moral sense or sensitivities. It helps to explain the ability and willingness of “ordinary men” to commit murder repeatedly.

The responses to the killing varied. Three main groups can be distinguished. The first group included those men who displayed particular zeal and brutality. In the killing squads they became known as “permanent shooters”. In the second group, the largest, were those who experienced a feeling of discomfort and or squeamishness at the task to which they had been assigned. They needed more time to become accustomed to acts of brutality and murder. The third and smallest group included those who made efforts to have themselves relieved of killing duties or who objected to a killing order.

No one who protested against the murder of the Jews or disobeyed a killing order was ever sentenced to death by the special SS and Police Courts. As a rule, they were relieved of their duties, transferred or demoted. Conversely, SS and policemen, military personnel and civilians both German and non-Germans who killed Jews, without authorisation or instruction, risked punishment, not for their act of murder, but for the infringement of SS jurisdiction.

Not all perpetrators were capable of carrying out assigned acts of murder. Some succumbed to feelings of nausea during massacres, especially at the sight of children being killed or at the opening and cleaning out of gas vans. As frequently happened, shots of poorly trained or nervous marksmen tore open the heads of their victims, spraying bone, brain matter and blood onto the faces, hands and uniforms of the murderers. Occasionally such poor marksmanship resulted in vomiting attacks or in skin eczema and other psychosomatic disorders. These patients were cared for in special wards and later in sanatoria and holidays resorts run by the SS.

From the outset, the architects of the “Final Solution” were concerned about the well being of the executioners. Clear instructions were given to ensure that members of execution commandos came to no harm. At all killing sites, coveted Schnapps and cigarette rations were distributed. Entertainment programs were offered to wipe out the impressions of Judenaktionen. A “festive” atmosphere surrounded the killings. Lively evenings or noisy dinner parties were particularly popular. Held in barracks or local inns, often prepaid by Jewish money, they rapidly turned into Saufabende, drunken orgies. In a secret SS-order of 12 December 1941 – a key document of the Holocaust – Heinrich Himmler proclaimed :

“It is the holy duty of senior leaders and commanders personally to ensure that none of our men who has to fulfill this heavy duty should grow coarse or suffer emotional or personal damage thereby. This task is to be fulfilled through the strictest discipline in the execution of official duties, through comradely gatherings at the end of the days, which have included such difficult tasks. The comradely gathering must on no account, however, end in the abuse of alcohol. It should be an evening on which, as far as possible, they sit and eat at table in the best German domestic style, and music, lectures and introductions to the beauties of German intellectual and emotional life occupy the hours. To relieve men at the appropriate stage from such difficult missions, send them on leave or transfer them to other absorbing and fulfilling tasks – possibly even to another area – I regard as an important and pressing matter”.

Heinrich Himmler spoke repeatedly of the “heaviest task” the SS had to perform to exterminate the Jews and of the Anständigkeit, the decency that had been preserved in spite of it. Indeed, it is this monstrous marrying of murder and morality, of criminal behaviour and self-fashioned decency, which is at the core of the perpetrators’ mentality. Within the framework of this particular brand of Nazi ethics, a complete new understanding of decency was created.

The philosopher Hannah Arendt spoke of the banality of evil, others of the normality of crime. Almost all “ordinary men” – murderers – demonstrated an ability to make a smooth transition back into their day-to-day existence and to lead normal lives, having been executors of mass murder. Expressed differently – and this is one of the most disturbing insights of the Holocaust – the murderers were spared the lifelong traumatic symptoms that were and remain the dreadful legacy of the surviving victims.

Current Concerns

The experience of the Holocaust, the slaughter of 6 million men, women and children, and the indifference of Gentile society, shattered Jewish faith in the European Diaspora. Further, after liberation, survivors were often treated with suspicion and hostility; especially those who attempted to retrieve property and assets stolen by Nazi authorities or rapacious neighbours. Many turned their back on Europe seeking new homes in the land of Israel or elsewhere, including Australia.

The majority of Nazi killers murdered with impunity. With few exceptions, those who did stand trial showed no remorse, maintaining their innocence and ignorance. Today, six decades after the murders, the last trials are drawing to a close. In most countries, as in Australia, the Nazi war crimes debate is already a thing of the past and has given way to the problem of how to prosecute modern war criminals and genocidal killers.

Horrific crimes against humanity have continued unabated since 1945. Neither the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg and subsequent trials, declarations, nor statutes or extensive media coverage nor “early warning systems”, let alone academic discourse on the subject, has acted as a deterrent. Today, unlike during World War II, most atrocities are carried out before the eyes of the world community. The perpetual bombardment of images of heinous crimes and their consequences evokes spontaneous outrage and bewilderment, together with a sense of powerlessness, that all too swiftly gives way to indifference and silence, the basic pattern displayed by bystanders and bystander nations during the Holocaust.

Ethical and legal frameworks have been established in recent years to investigate and prosecute crimes against humanity, genocide, and aggression, most notably by the UN War Crimes Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and for Rwanda, the International Criminal Court and the Khmer Rouge Tribunal for the Cambodian genocide, but it remains to be seen how successful these instruments will be to enforce the rule of law.

And yet, there is another continuity unbroken by Auschwitz. At the dawn of the 21st century, the safe season for Jews is nearing its end. Racism, antisemitism and anti Zionism, reinvigorated by new stereotypes that go hand in hand with long-held prejudices, are on the rise again – almost everywhere. The growth industry of Holocaust denial is another alarming feature of the globalisation of the Holocaust.

In view of these current concerns, there seems little or no sense in appealing to lessons of history or in repeating again and again the phrase “Never Again”. If there is a lesson in the Holocaust then it is to show how comparatively easy it was in a dictatorial and racial regime and under war conditions to transform ordinary men into genocidal killers and how difficult it was to convert an army of bystanders and bystander nations to rescuers of Jews. More attention should be paid to the “Righteous Gentiles” as well as to those who dared to deviate from the norm, who resisted the orders to commit murder and, in doing so, preserved their humanity and moral integrity. Holocaust education must be firmly anchored in the teaching of democratic principles and humanistic values to reinforce and cement the commitment to social justice and human rights. This task is today more urgent than ever.

Yehuda Bauer, the pre-eminent historian of the Holocaust, argues that the genocide of European Jewry, unprecedented in history, has set the precedent for subsequent genocides and, in doing so, has become the symbol of genocide. He points to the events of September 11, 2001, to support his argument that the terrorist attacks against New York and Washington, DC, are changing our perception and understanding of the Holocaust. Radical Islamic fundamentalism, international terrorism, and genocidal campaigns alongside with hate ideologies and political or racially motivated universal utopias are a threat to humanity. As Bauer phrases : “We all are in the same boat: hence, the crucial importance of research into genocide generally and the Holocaust specifically”. The obligation to combat antisemitism, racism and fundamentalist terrorism remains an imperative in order to prevent genocidal situations and campaigns.

[This article first appeared in “Teaching History”, the Journal of the History Teachers Association of NSW, in June 2005.]

Emeritus Professor Dr. Konrad Kwiet is Adjunct Professor for Jewish Studies and Roth Lecturer in Holocaust Studies at The University of Sydney, and Resident Historian at the Sydney Jewish Museum